I began studying Mandarin as an undergraduate at Middlebury College, and was fortunate to be able to study abroad in China with the Middlebury C.V. Starr Schools Abroad program in Beijing and Kunming during January term and Spring term, respectively, of 2012.

I wanted to make the most of my study abroad experience, and to me this meant pursuing some kind of research project while in China. I was interested in designing a project that would bridge my academic interests in environmental sustainability with my personal interests in photography and youth engagement. Since I knew I would be studying in different parts of China, I submitted a proposal to Middlebury College’s Sustainable Study Abroad Grant program to conduct a comparative study on how Chinese youth perceive and value the environment, and was 1 of 3 students selected to receive grant funding to support my research.

PROJECT BACKGROUND

The world’s leading annual emitter of carbon dioxide and a country notorious for its air and water pollution and high-profile species extinctions, China also leads the world in clean energy investments (see IEEFA’s report here and Bloomberg NEF’s report here) and has witnessed an exponential rise in its number of registered environmental non-governmental organizations. Furthermore, the People’s Republic of China’s 12th Five-Year Plan (FYP) for National Economic and Social Development (2011-2015) lists environmental protection as one of its three key themes, within which reducing pollution, increasing energy efficiency, and ensuring reliable clean energy sources rank as top priorities.

While targeting specific environmental issues under the FYP allows the Chinese government to manage priorities, the youth of China today will necessarily determine the ways in which China’s shifting fabric of environmental ethos and actions are carried forward into the future. To what extent do Chinese citizens, especially those of the younger generation, also identify with these objectives? Furthermore, what kind of space has a younger generation — that has been taught to associate activism with censorship (see this article about young people in China grappling with what civic engagement, activism, and social change means to them) — been given to develop their own priorities around environmental concerns? What have Chinese youth come to value with respect to their immediate environments? How might these perspectives differ depending on geographic and sociocultural contexts? Finally, how might these perspectives be extended to gauge China’s future environmental prospects?

My research project set out to bring some clarity to these questions.

METHODOLOGY

My study participants, all university-aged and native Chinese, were selected from three different sites:

- Beijing Institute of Education in Beijing, China’s political and economic center to the north;

- Yunnan University in Kunming, a developing city in China’s southern Yunnan Province, itself a designated Global Biodiversity Hotspot; and

- Danuohei (大糯黑), a rural Yi ethnic minority village in Yunnan Province about 75 miles southeast of Kunming.

At each site, I distributed disposable cameras to four individuals and asked them to take pictures of anything that represented or defined what the environment meant to them. I hoped that this more free-form approach, based on visual environmental representations, would give them the opportunity to creatively define their own perceptions of things in the environment that they valued. As Collier and Collier (1986) write in Visual Anthropology: Photography as a Research Method:

“Images invite people to take the lead in inquiry.”

My intention was to provide my study participants the tools with which to capture and communicate their own thoughts.

I also debriefed with each of the individuals after they had taken their photos about their motivations behind taking the photos that they did, and about their understanding of environmental thought and movements in modern-day China. Finally, I interviewed staff at Friends of Nature, China’s oldest environmental non-governmental organization headquartered in Beijing, and the World Wildlife Fund’s (WWF) Kunming office on similar topics.

RESULTS

Here’s a figure that summarizes the photographs that the study participants from each of Beijing, Kunming, and Danuohei took, by subject matter:

In order, the top 3 subjects photographed by:

- Beijing participants were trash, greenery/plants, then air quality;

- Kunming participants were water quality, trash, then buildings/construction; and

- Danuohei participants were materials (stone, wood, straw), embroidery/handicrafts, then animals.

Here are some examples of the photos that the study participants took:

Trash in Beijing

Polluted water in Kunming

Materials in Danuohei

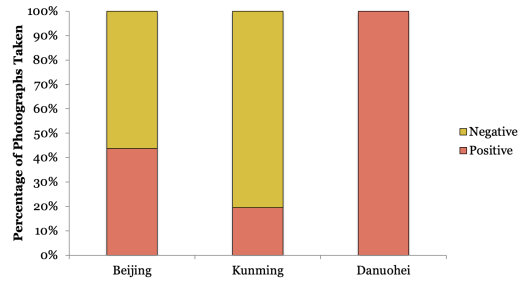

My discussions with the study participants were particularly illuminating. They allowed me to retroactively code each photo they took as being reflective of either their “positive” or “negative” view of the natural environment:

All photos by the Danuohei participants were photos that the participants took out of “positive” reactions to their natural environment. Frequently used descriptors of these photos included “home,” “cultural identity,” “livelihood,” and “responsibility” — as in a responsibility for resource conservation and the preservation of the current state of their hometown village. Meanwhile, negative photographs dominated those photos taken by the Beijing and Kunming participants. Frequently used descriptors of these photos included “dirty,” “everywhere,” and “no management.”

After synthesizing the photos alongside my discussions with the study participants and and environmental professionals working at environmental non-profits in China, I drew a few general conclusions from my research:

- Spatial immediacy is important when Chinese youth determine the extent to which something is important to them in their environment. Beijing and Kunming study participants took more photographs related to environmental issues considered common in many of China’s larger cities – construction and infrastructure development, waste treatment and disposal, water and air pollution – than the Danuohei villagers, who tended to photograph the natural resources that form the foundation of village life. Indeed, “If people are affected, then they’ll care,” said my contact at Friends of Nature. The implication here is that Chinese youth may feel less compelled to engage with environmental issues that are more detached from their immediate lives and surroundings.

- Discontent with both the Chinese government and Chinese society is common. Most study participants claimed that, while the Chinese government must be held responsible for ameliorating major problems such as pollution and waste management, the government has failed in establishing credible regulatory divisions to achieve this end. Participants also claimed that, while Chinese citizens must assume responsibility for environmental action as well, many lack the basic yet necessary environmental education to do so. An implication of this finding is that perhaps this missing sense of civil society coupled with a lack of environmental education are also important barriers for China to address before strong, interconnected, and mass-based environmental movements can ultimately be realized.

WHERE CAN YOU READ MORE?

I submitted a final research paper that summarized my work, and also presented my work along with my fellow grant recipients in April 2013 at the Rohatyn Center for International Affairs on the Middlebury College campus.