In Summer 2011, I was selected to take part in the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Science Undergraduate Laboratory Internship (SULI) program, which offers research experiences for undergraduate students who are interested in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields at DOE laboratories across the country.

I spent the summer at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL) in the beautiful hills of Berkeley, California. I was a member of Dr. Caroline Ajo-Franklin’s research group, which explores the nanoscale interface between living microbes and inorganic materials at LBNL’s Molecular Foundry, and worked on a project to improve geologic carbon sequestration with direct mentorship from Dr. Jenny Cappuccio.

PROJECT BACKGROUND

What is geologic carbon sequestration and why does it matter?

Rising atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) levels are driving our current global climate crisis. Geologic carbon sequestration — the injection of CO2 into deep underground geologic formations for long-term storage — is being increasingly recognized as a necessary tool in the grand toolbox of large-scale climate change mitigation efforts.

Under the high pressures and temperatures of deep geologic formations, gaseous CO2 is naturally converted into solid calcium carbonate through carbonate mineralization processes. However, carbonate mineralization can occur over long geologic time scales, which poses potential hazards of inadvertent CO2 release and subsequent threats to human health and the environment. Microorganisms have been known to play major roles in accelerating carbonate mineralization, although more research is needed to better understand the mechanisms underlying such mineralization.

Our research focus

The goal of our research was to systematically investigate these mineralization mechanisms by studying calcium carbonate formation in the presence or absence of microbes with various surface features, with potential applications for enhanced CO2 sequestration.

METHODOLOGY

We primarily worked with two microbial species capable of displaying crystalline surface layer (S-layer) proteins: Lysinibacillus sphaericus, a common soil bacteria, and Caulobacter vibrioides, which commonly inhabits aquatic environments. We engineered C. vibrioides variants that secreted either just S-layer proteins or S-layer proteins with additional peptide sequences which introduced additional positive, negative, or neutral surface charges at the nanoscale. We then observed calcium carbonate crystal formation in the presence and absence of these microbes.

RESULTS

The presence of bacteria accelerated calcium carbonate mineralization, when compared to purely abiotic conditions. Calcium carbonate mineralization was further accelerated in the presence of S-layer-secreting bacteria and bacteria engineered to display additional negative charge on their S-layers, when compared to non-S-layer secreting bacteria.

Below are some figures that illustrate our findings.

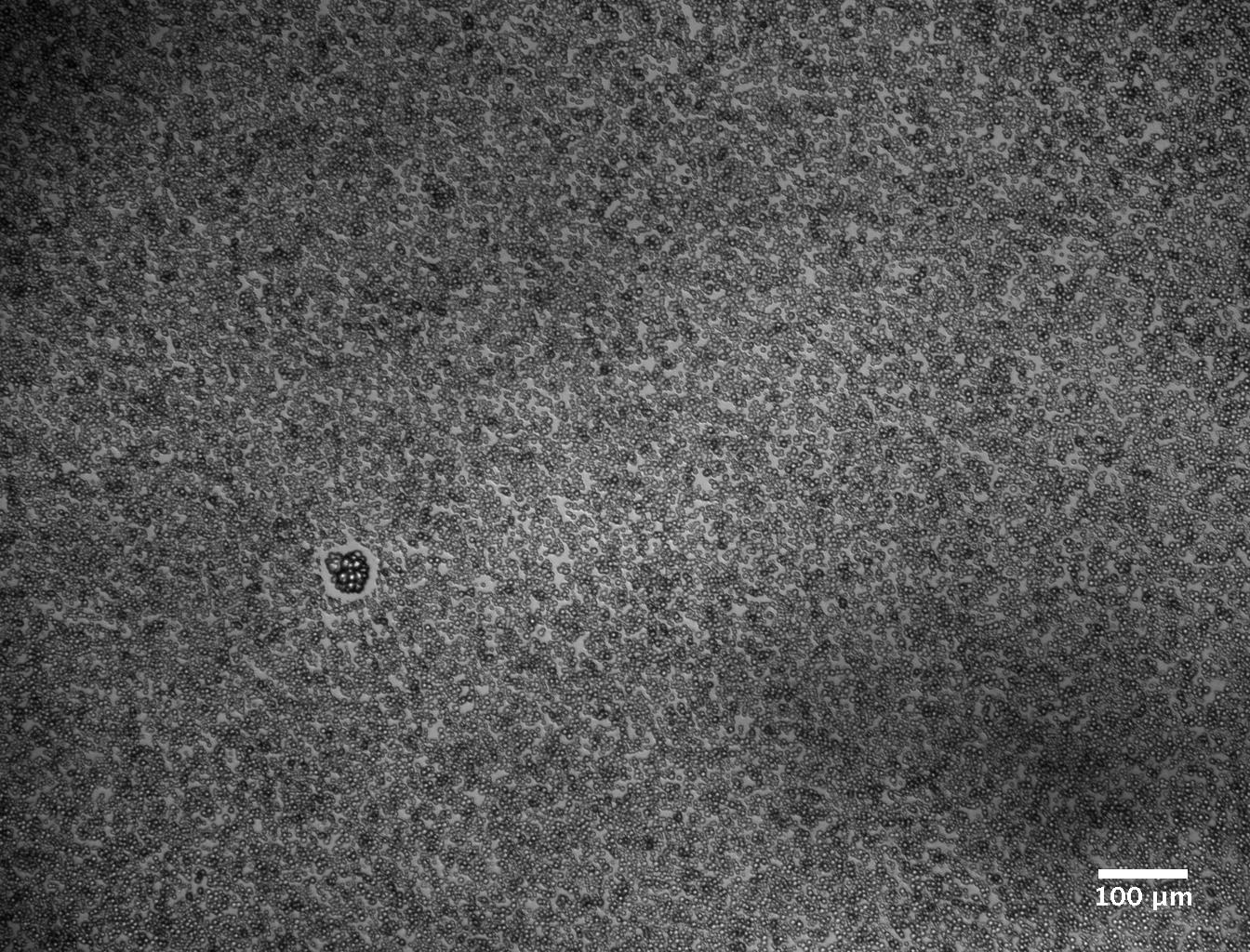

Here’s a representative bright-field optical microscopy image of calcium carbonate crystal formation after 24 hours under a standard set of ambient conditions:

What you’re looking at is largely amorphous calcium carbonate. Compare the above figure to the type of calcium carbonate crystal formation we observed after 24 hours under the same standard set of conditions, this time with the added presence of bacteria that do not feature S-layers:

You can see that the calcium carbonate has mineralized into larger, more stable vaterite formations (the flowery-looking formations).

Finally, here’s the type of calcium carbonate crystals we observed after 24 hours under the same standard set of conditions, this time after adding the bacteria we engineered to display additional negative charge on top of their S-layers. The formations you see are calcite, which is the most stable polymorph of calcium carbonate:

We conducted further analysis to better understand the mechanism underlying the patterns we were observing — namely, that bacteria, particularly bacteria with S-layers and S-layers with additional negative charge, were facilitating calcium carbonate formation. Our analysis found that, when compared to bacteria without S-layers, bacteria with S-layers and S-layers with additional negative charge demonstrated significant preferential binding to calcium, an indication that S-layer surfaces can better recruit positively charged calcium ions to increase local calcium ion concentrations, reduce the activation barrier needed for calcium carbonate nucleation, and therefore facilitate crystal formation.

Optically, we did observe bacteria clustering on or near mineral surfaces, particularly at stepped crystal edges, which are critical sites of material deposition for crystal growth:

Ultimately, our research indicated that microbes can enhance and accelerate calcium carbonate mineralization and that microbial S-layers in particular appear to achieve this by offering ordered, negatively charged nucleation sites for calcium carbonate to form, with the implication that microbes with tuned surface layers can be used to enhance carbon dioxide sequestration as stable mineral carbonates.

WHERE CAN YOU READ MORE?

At the end of the program, I presented our research findings to my lab mates, as well as through a poster session to the broader DOE SULI program. My mentors presented our research to the broader scientific community after my program’s end, and my research also contributed to additional research on S-layers for heavy metal bioremediation.